By Milena Karen Bär & Dr. Kristjan Jespersen

◦ 5 min read ◦

The first step of the EU Action Plan of Sustainable Finance

New regulations in the ESG sphere are on the upswing especially in the EU. To reach the commitments of the Paris agreement, the European commission has introduced new regulations as the first step of the EU action plan: the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). The first level was already implemented on March 10th 2021. The implementation of the regulation is an extension of the EU Taxonomy, amending the issue of greenwashing among financial market participants (FMPs). The new reporting requirements are profound and will be fundamental to almost any participant on the European markets, whether you are in the financial, or for that matter, the manufacturing, retail, service, non-governmental and governmental sectors.

The European Union’s experiment in defining what is sustainable and in directing markets to more sustainable investments, is putting pressure on market players to keep up with the quickly paced regulative developments.

Two main issues are subject to the debate of appropriate implementation of the SFDR, which entail firstly, the uncertainty of product classification and secondly, the complexity of data collection and usage. Not only all those affected must revise their whole reporting regime, but the EU must ultimately also ask itself the question whether the regulations have nurtured the intended behavior of the market.

SFDR and PAI in general

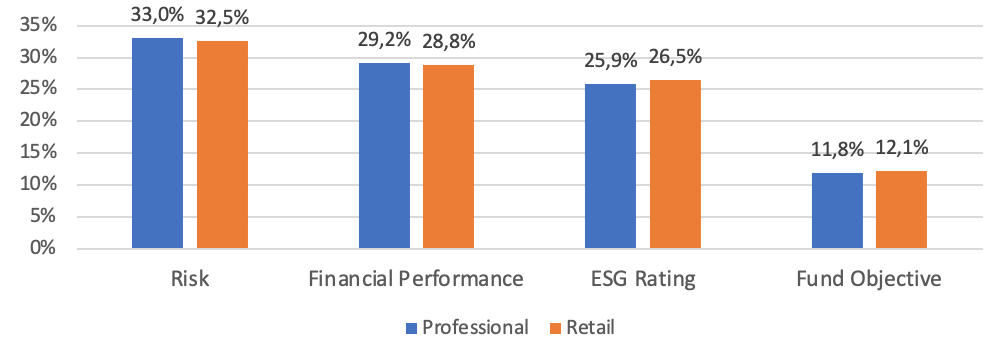

The SFDR is implemented to benefit clarity for investors and asset managers, by improving their ability to compare investment options from a sustainability point of view. Therefore, the SFDR provides a collective framework, which requires FMPs to disclose the way they are taking sustainability risks into consideration in its business practices (entity level) and in its financial products (product level) in a consistent and curated fashion.

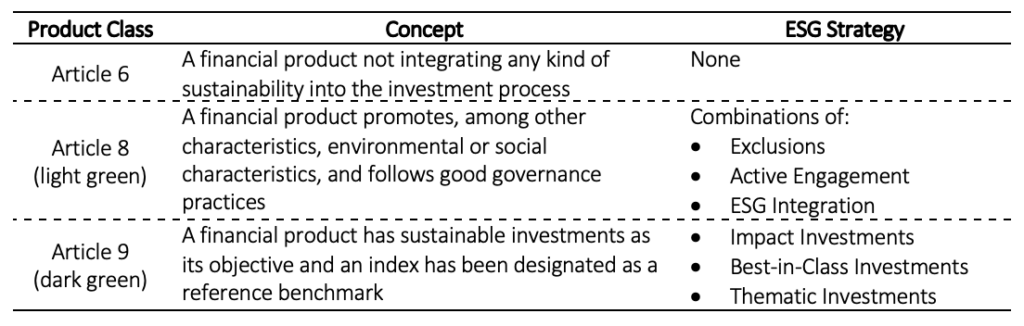

Additionally, the FMP must report on the principal adverse impacts (PAIs). These contain a list of mandatory and voluntary adverse impact indicators, covering environmental issues and the field of social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption, and anti-bribery matters. Based on the SFDR disclosures, the product offerings can then be classified within the three categories referred to as article 6, 8, or 9 products, which indicate the level of greenness ranging from article 6 which does not consider sustainability at all, and article 9 which must follow a sustainable objective.

Issues arising

The objective of the EU Action Plan and the SFDR is to reorient financial capital towards sustainable products and solutions. However, certain challenges raise the question whether the regulation can indeed serve this very purpose. To begin with, the mechanics of defining light and dark green products is lacking a foundation and boundaries, allowing for self-interpretation. The differentiation between light and dark green is ambiguous, and thus instead of serving as a guideline, is increasing uncertainty about what the articles constitute.

Issue 1: The color palette of light and dark green assets

One might say, just as colors are perceived differently by each human, light and dark green assets can be various shades of green and thus, on completely different sustainability levels. The regulatory product declaration is not yet methodologically sound, the lack of distinction of the two leaves room for interpretation of the classifying entity. So far, no specific classification mechanism or framework exists that FMPs can apply and are thus able to approach the classification in more prudent or more generous ways. One may put a product under article 8, while at the same time another FMP might classify the same product under article 9.

It seems the darkness of green is up for preference of the asset manager. Although there may be consensus that exclusion strategies are minimum requirements for both classifications, the scope of exclusion criteria varies greatly. This allows for instance some article 9 products to still be involved in controversial actions, such as fossil fuels, tobacco, and controversial weapons.

Secondly, collecting relevant data poses a challenge, and even if data is available, its variety used to report on the SFDR and the PAI, makes the curation inconsistent and biased. An investor might have a full PAI statement to assess its investment, but can one trust the accuracy and relevancy of the data?

Issue 2: Quality of data fades into the background

The PAI statements can be considered as a curation tool for asset managers (AM) to filter for the most sustainable products and steer capital towards green transition products. Even though the framework of the PAI indicators might be well structured, what is important is the quality of inputs. But the complexity of PAI indicators poses challenges for almost any market participant. PAI data is often not readily available, and this is aggravated by the fact that this data needs to be tracked on a continuous basis. Data collection and maintenance can thus become costly for the underlying portfolio companies. Large cap companies can overcome this issue, but small cap players are confronted with an expensive data collection for a wide range of PAIs or with the need to opt out due to lack of data availability.

Hence, large cap companies may gain competitive advantage without indicating greater performance. AMs incorporate the PAI data in a screening process to extract the most responsible products of the investment universe. However, some asset managers are simply selecting those assets with the highest coverage of PAI indicators. Again, leaving large cap companies in favor, although the high coverage of indicators not necessarily correlates with sustainable performance. The quality of the data fades into the background and investments with higher sustainable and financial potential can be missed out on. Ultimately, businesses leading the market today, may stay right where they are, without enabling opportunities for more innovative and greener solutions.

While the intention of the SFDR is to further restrict greenwashing, current practice may raise the question whether there are still loopholes for FMPs to label their products as greener as they actually are. Although we have seen regulations to be great drivers of sustainable corporate and market action, guidelines must be established to provide more specific and narrow pathways. The weak structure of product classification and the complexity of data may prevent the SFDR to provide a framework for more coherent and uniform information of sustainability risks. The European commission must clarify actual implementation practices, to enable the entire effect of capital reorientation. No market participant is exempted from the need to be aligned with the SFDR today, as new waves of regulations will follow, and it is to start paddling.

About the Author

Milena Karen Bär is a student researcher in ESG and Sustainable Investments, absolving a Master’s degree in applied Economics and Finance at Copenhagen Business School. Her research projects are mainly within the field of ESG metrics and regulation, with a focus on the investor’s side.

Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies on the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.

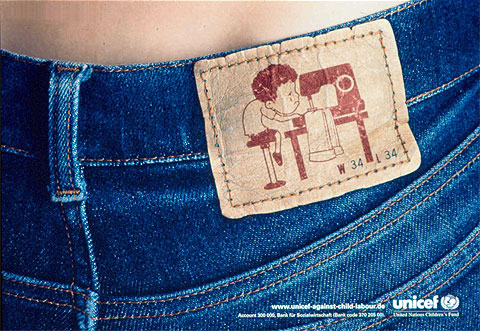

Photo by Freddie Collins on Unsplash

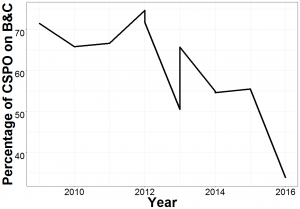

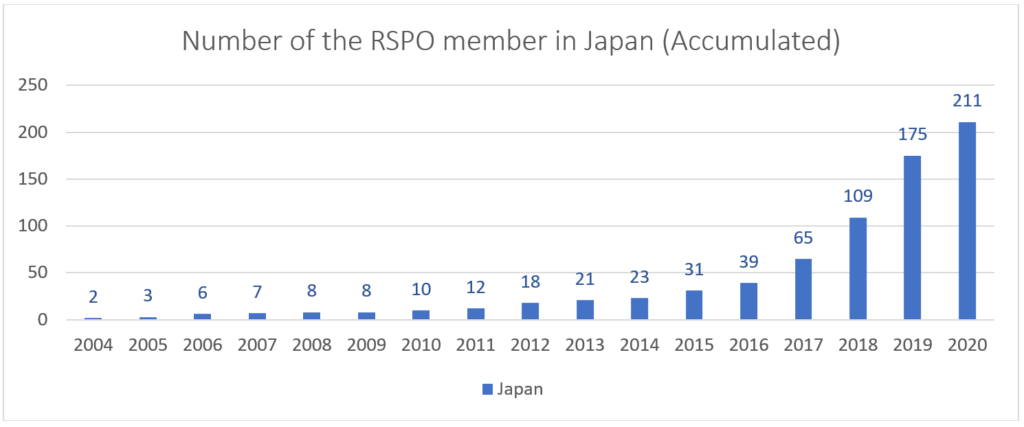

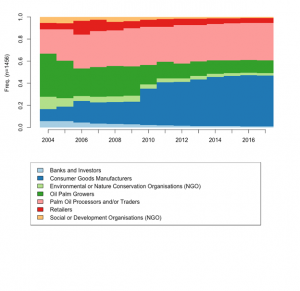

Figure 1: Composition of RSPO membership, by year (RSPO Website Data). Credit: Mikkel Kruuse and Kaspar Tangbaek.

Figure 1: Composition of RSPO membership, by year (RSPO Website Data). Credit: Mikkel Kruuse and Kaspar Tangbaek.