Theory of Change – Evaluating Supply Chain Outcomes

By Kamilla Hvid Andersen, Eileen Ryll, Dr. Caleb Gallemore and Dr. Kristjan Jespersen

Due to globalization, supply chains are becoming increasingly complex, challenging national governments’ regulatory capacity, or, perhaps, political will. Amid these “governance gaps” some private-sector organizations have begun setting voluntary standards promoting sustainable production practices. As they are not backed with legal force, private standards must demonstrate both positive impacts, credibility and inclusive decision-making to be perceived as legitimate in the eyes of external observers and member firms. Due to the complex and interrelated nature of sustainability issues, it can, however, be difficult to relate outcomes back to activities of the standard setting system.

To monitor their programs and evaluate their impact, many standard-setting organizations have adopted a Theory of Change (ToC).

Based on Carol Weiss’s theory-based evaluation approach, a ToC is a cause-and-effect illustration that makes explicit often implicit beliefs and assumptions about how different actions should generate impacts.

Evaluating impacts then requires collecting data that show how the proposed causal sequence plays out and, if discontinued, where it broke down. On this account, the ToC is necessary because practitioners often rely on tacit knowledge or even guesswork, rarely articulating the conceptual foundations of their actions explicitly.

ISEAL – The Standard for Standards

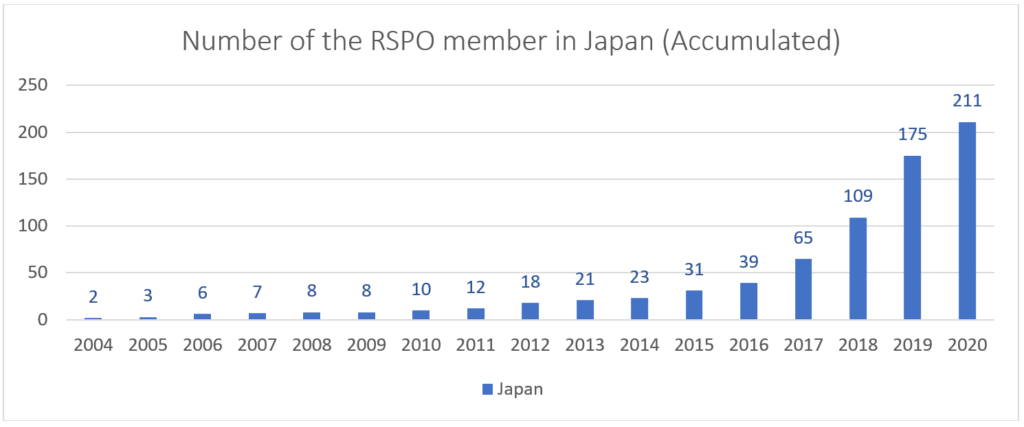

The ISEAL Alliance has been a key ToC promoter for many major sustainability standards. The organization is in essence a benchmarker for certification systems, working to disseminate better practices across sustainability standards. While the organization has a relatively small membership, its members include prominent standards like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). Its Impact Code strongly encourages, though does not require, a ToC as the foundation for robust Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E).

While couched in an M&E framework, ISEALs’ framing of a ToC as a way to articulate building blocks for long-term goals also links it to strategic planning. For the organization, a ToC is both product and process. As a product it maps out what to measure to assess a standard’s impact. As a process, it can help define a shared vision of how the standard should be making change, helping get member and observer buy-in on its strategic trajectory.

Case in Point – RSPO

The RSPO is a good example of how ToC procedures can influence organizational operations. Following ISEAL recommendations, the RSPO constructed an elaborate ToC in 2017. While its stated primary goal of making sustainable palm oil the global norm has remained since the standard’s early days, the ToC outlines the strategies deemed necessary to achieve this vision. By explicating the assumptions behind its actions, the RSPO’s ToC is simultaneously an M&E tool and a strategy. Though, like ISEAL, the RSPO introduced the ToC as an impact evaluation tool, the process generated critical discussions on the organization’s shared vision and explicated previously implicit beliefs regarding what making sustainable palm oil the norm actually means and how it could be achieved.

Because ToCs have both M&E and strategic planning components, responsibility for their development and implementation should not reside solely in M&E departments. Rather, effective ToC processes should include the whole organization and external stakeholders, requiring strategic decision-making support. Continuous feedback from all actors implementing elements of the ToC into their daily work can be valuable to highlight shortcomings of the ToC in place and guide future strategy reviews.

The Mechanics of TOC

A ToC process includes two broad phases. In the first, relevant actors develop or refine a shared vision and outline causal sequences necessary to achieve it. In the second, actors must incorporate the ToC into day-to-day routines.

The ToC as it emerges from the first phase is an intermediate outcome, part of a continuous learning loop that can be influenced by other processes surrounding the organization. It also may trigger other processes, as was the case within the RSPO when the ToC heavily informed another strategy document outlining member responsibilities across the value chain. The division between these phases, of course, is blurry, and it is always possible to re-evaluate and re-model the intermediate ToC, making the process iterative. All this work goes far beyond simple M&E, a lesson the RSPO learned the hard way, at first significantly underestimating the effort necessary to develop its ToC, regarding is simply as mapping out what was already there.

The Role of Interactive Adaptivity in Supply Chains Evaluation

Based on the example of their use by ISEAL and the RSPO, ToCs can serve several purposes:

- First, they can support strategic planning while structuring strategic reconsiderations over time. Their iterativity might make it particularly important for organizations to revisit their ToCs before strategic re-alignments or in times of upheaval.

- Second, in a complex field that spans multiple stakeholder groups, which as is case with the RSPO, most likely have divergent underlying assumptions, the ToC process can help illuminate blind spots. To be effective, the ToC needs to be inclusive of as many of the actors affected by the organization’s activities as possible.

- Third and more prosaically, a ToC, while more than impact evaluation, can support evaluative work, serving as the backbone for M&E activities.

About the Authors

Caleb Gallemore is an Assistant Professor in the International Affairs Program at Lafayette College. He holds a Ph.D. in Geography and within his teaching, he focuses on southeast Asia, global land use, sustainability, research methods and geographic information science.

Eileen Ryll graduated from CBS with a degree in MSc. Business, Language and Culture with a focus on Diversity and Change Management. She has previously studied Business and Cultural Studies in Germany and Sweden. Her main interests are organizational strategy and intercultural encounters.

Kamilla Hvid Andersen studied her bachelor’s and master’s degree at Copenhagen Business School. In June 2020, she graduated from the MSc. in Business, Language and Culture with a specialization in Diversity and Change Management. Her personal interests include sustainability, intercultural communication, and organizational change.

Kristjan Jespersen is an Assistant Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.

Photo by Jungwoo Hong on Unsplash