How local norms may be able to help drive the spread of voluntary programs – the case of the RSPO in Japan.

By Hattaya Rungruengsaowapak, Caleb Gallemore & Kristjan Jespersen

There has been an explosion in voluntary programs targeting value chains’ negative social and environmental impacts (Green, 2013). Working across boundaries, however, is challenging, and requires bridging different business cultures and moral expectations. Tensions and consequential misunderstandings between members from different countries are common.

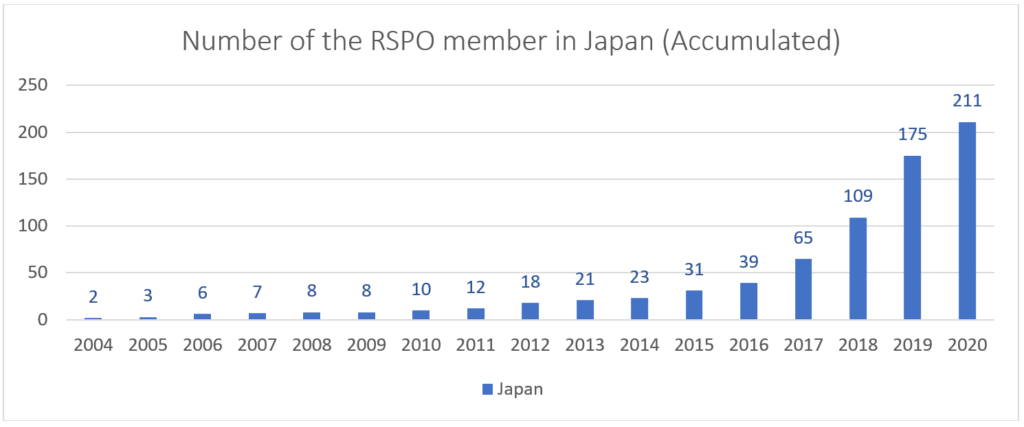

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm oil (RSPO) is a good example. It has seen a five-fold jump in Japanese membership in just five years, going from under 40 members in 2016 to more than 200 in 2020. This has happened in the absence of meaningful governmental support or even consumer demand, making it a particularly interesting case.

The RSPO was founded in 2004, led by WWF, Unilever, and some upstream players in the palm oil value chain. Its objective is to incentivize sustainable palm oil production using voluntary certification. Although oil palm is one of the most efficient oil-producing crops, its growing consumption has led smallholders and large agribusiness to convert tropical forests to plantations, causing habitat and biodiversity loss, greenhouse gas emissions, and wildfires.

While the RSPO welcomed its first Japanese members the year of its founding, it only recently saw memberships skyrocket, despite limited concern among Japanese consumers. These developments took place in three main phases.

Phase 1 – Testing the waters (2004 – 2011)

For nearly the first decade of the RSPO’s existence, Japanese membership growth was sluggish. Japanese companies that joined the RSPO early on mostly relied on international markets for a significant part of their business.

These companies included major trading houses like Mitsui & Co., Ltd, and consumer goods manufacturers like Kao. Multinational companies headquartered in the West, such as Unilever and Walmart, also implemented sustainable palm oil commitments in Japan, but these actions had little impact on their Japanese suppliers.

Some smaller Japanese companies also joined the RSPO in this phase, in response to some niche consumer demand. These niche actors, however, did not scale up demand across the country.

Phase 2 – Setting the groundwork (2012 – 2016)

Between 2012 and 2016, a larger number of Japanese firms joined annually than in the previous period, though never more than ten in any given year. In 2012, when Tokyo became a host city candidate for the ultimately ill-fated 2020 summer Olympics, the RSPO began directing more attention towards the Japanese market.

A central goal was to convince the local Olympic Committee to include the RSPO in their official sourcing code. According to an informant, the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) began to hold corporate sustainable palm oil workshops the same year. Other events helped boost RSPO recognition during this period. For example, in 2015, the Japanese government officially adopted and started to promote Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In the same year, the Consumer Goods Forum, a global network of manufacturers and retailers, issued its Sustainable Sourcing Guideline. T

The period closed with the largest sustainable palm oil event in Japan to date – the RSPO Japan Day 2016 – where RSPO advocates draw on these events and urged more than 350 attendants from major companies in Japan to become members.

Phase 3 – Takeoff (2017 – 2020)

By 2017, many companies using palm oil in their products were aware of the issues associated with oil palm production. Two powerful actors, however, were central in pushing firms from awareness to action. The first was the Tokyo Organising Committee for the Olympics Games (TOCOG), which officially included certified sustainable palm oil in the Games’ sourcing code. The other was AEON, the biggest retailer in Japan and a member of the Consumer Goods Forum, who vowed to procure 100% certified sustainable palm oil for more than 3,500 of its house-brand items by 2020.

These moves forced several suppliers to seek certified sustainable palm oil sources. Thankfully, RSPO advocates ongoing work had led to the creation of various programs to support Japanese firms’ RSPO membership.

The RSPO opened a Japan office in 2019, and at around the same time, the WWF started Japan Sustainable Palm Oil Network (JaSPON). With suppliers already prepared, some downstream firms found it more attractive to join the RSPO at this time. Competitors of existing RSPO members, in turn, started making sustainability commitments for fear of public criticism.

Throughout the RSPO’s development in Japan, end-product consumers’ pressure has had a limited impact on firms’ decisions to join. The pressure to conform to sustainability standards created by the advocates targeting lead firms with vast supply networks, however, appears to have accelerated RSPO’s market growth. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is the Japanese norm of long-term relationships between firms with buyers-suppliers ties, which, in some cases, include cross-shareholdings between them. Such a group of firms is alternatively known as a keiretsu.

Although keiretsu is not well defined, it is generally referred to as personal, capital, and business relationships in relation to business transactions (Yaginuma, 2014). Collective commitments commonly observed in firms within a keiretsu may have made lead firms more likely to support their suppliers’ efforts to get certified, rather than switching to other suppliers.

Even though RSPO memberships in Japan have increased rapidly, it is unclear whether this will translate into substantial increases in certified sustainable palm oil uptake. Many manufacturers’ suppliers are relatively small. They are often sensitive to any additional costs, and limited bargaining power with which to procure certified oil.

Moreover, since end consumer awareness continues to be low, businesses receive no additional remuneration for their sustainability investments, which may force them to cut costs elsewhere.

These problems aside, Japan exemplifies an intriguing model of sustainable business practice adoption resulting from the local business norms. Thanks to the strong ties between Japanese firms, the RSPO was able to establish a foothold in the industry despite the lack of demand for sustainable palm oil from the civil society – a sharp contrast to patterns in the West.

References

Green, J. F. (2013). Rethinking private authority: Agents and entrepreneurs in global environmental governance. Princeton University Press.

RSPO. (n.d.). Members. Retrieved 2020-08-09

Yaginuma, H. (2014). The Keiretsu Issue: A Theoretical Approach. Japanese Economic Studies.

About the authors

Kristjan Jespersen is an Assistant Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.

Hattaya Rungruengsaowapak is a fresh graduate from Business, Language and Culture at CBS. She has extensive experience in Japan, especially within supply chain and sustainability from a leading consumer goods manufacturer prior to her studies at CBS.

Caleb Gallemore is an Assistant Professor in the International Affairs Program at Lafayette College. He holds a Ph.D. in Geography and within his teaching, he focuses on southeast Asia, global land use, sustainability, research methods and geographic information science.

Photo by Nazarizal Mohammad on Unsplash