By Jan Bauer.

- MSC reviews six months of its sustainable food policy

- Setting defaults can be highly effective

- Guiding principles for the “right” defaults are not always easy to determine

During the summer 2017, the Department for Management, Society & Communication (MSC) at CBS hold a competition among its members to come up with ideas to foster sustainable behaviour within the daily work-life of the department. In addition to talking the talk in lectures and research, MSC hosts the CBS center for Corporate Social Responsibility, we also wanted to walk it.

Among many interesting submissions, the newly founded sustainable infrastructure task force (SIT) awarded the best idea, based on the potential impact and the feasibility of application within MSC. An idea to reduce the consumption of meat was declared as the winner. According to many studies, the reduction of meat reduces CO2 emissions and is associated with various health benefits.

Despite this evidence, banning meat in the department would have certainly and rightfully created substantial backlash. Banning meat would have unlikely been supported by a majority of the department members or its leadership as it can be arguably considered as an overly strong infringement of individual freedom.

Behavioural policy and the power of defaults

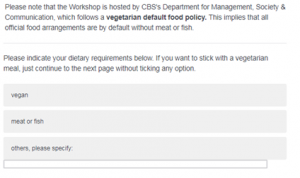

Based on a behavioral policy approach, the new food policy, publicly discussed in a department meeting and implemented in October 2017, ultimately changed the choice architecture of the way people order meals for meetings and events. For a trial period of six months, all meals became vegetarian by default; meaning that people get a vegetarian meal unless they actively opt-out and order a meat-based dish with a short email reply or by ticking a button (see example from a recent workshop invitation).

This idea is based on the principle of libertarian paternalism, which aims to steer peoples’ behaviour without restricting the freedom of choice and has been famously advocated by our colleague Cass Sunstein.

The power and controversy about purposefully setting defaults is often discussed in the context of organ donation. There is little doubt about the fact that people’s inertia to register as a donor can be linked to preventable deaths under the opt-out rule. The Netherlands recently change the default on the issue, but not all countries are expected to follow their example.

Predominant support for a sustainable default rule

The trial period of our food policy helped to understand the difficulties of implementing such a policy, e.g. what to do when you cannot ask participants. But it also aimed to collect data on how many vegetarian and meat-based meals were ordered. After the end of the trial period, a survey was conducted to elicit peoples’ attitudes towards and experiences with the policy.

More than 90% of the self-reported food orderings were vegetarian and the survey revealed that a majority supports to expand the policy beyond the trial period. However, the policy was not exclusively received with praise. Different concerns were raised about the policy, including the perception not feeling free to publicly speak up against such an initiative aimed and officially framed to “save the planet”.

Guiding principles: scientific evidence or democratic process?

I am confident that this pilot project will resolve its remaining issues, but the process itself has been a valuable learning experience and sparked some reflection. One issue is the rather simple question on what guiding principle should the default be selected in such an example. Two ideas come to mind instantly: assuming there is corporate interest in the health of employees and low CO2 emissions, the scientific evidence suggests that the vegetarian default should be the preferred way. However, decisions based on naturally broad scientific claims might miss important case-specific aspects, neglect the (corporate) culture and individual preferences.

Alternatively, setting the default by a democratic process might suffer from limited debate for such a morally loaded topic and individual biases against the abstract value of one’s own long-term health or reducing global warming. In principle, the aim should be to maximize overall welfare and nudge people to be “better off as judged by the themselves”. For reasons outlined above, it is not always easy or even fully clear, how and when individual judgement of such a policy should be assessed.

Judgement at the right time

When it comes to the food itself, having the light, vegetarian meal could be judged as less appealing before or during lunch when being extremely hungry, but evaluation might already change shortly after the meal. Reflecting on a meal in a satiated state can alter the importance of different aspects. Research suggests that hunger shifts preferences towards more palatable and less healthy foods, but also repeated exposure to a specific food increases preference for it. Hence, only 30 minutes could make all the difference, but potential benefits to health and environment might manifest in 30 years and only by then alter retrospective evaluation of such a policy.

Even though there is no natural default, most people like eating meat despite potential adverse health effects, including myself, which makes justifying any default rule difficult. In our case, all approaches we tried point towards the same result, which makes us hopeful to do the right thing. A decision to prolong the experimental policy by another year was recently made in the Department Forum. However, it is important to keep in mind that at its worst, this specific policy presents a die-hard meat lover with a vegetarian meal that he forgot to opt-out of – a hopefully rare event I am nevertheless sorry for.

Jan Bauer is Assistant Professor at Copenhagen Business School and part of CBS’ Governing Responsible Business Research Environment. His research interests are in the fields of health economics and consumer behaviour. As part of the Nudge-it Project, he focused on fostering healthy food choices of children and adults.

Photo: courtesy of Felix Bärmann.