By Fumiko Kano Glückstad

◦ 6 min read ◦

It is widely acknowledged that a plant-based diet is healthier than an animal-based diet (Willett, et al. 2019). However, a group of Japanese researchers recently published a thought-provoking article demonstrating that a lower diet-related Greenhouse gas emission (GHGE) has generally resulted in an inadequate nutrient intake among Japanese adults (Sugimoto et al. 2020).

Their results seem to support the fact that the Japanese Government has excluded any dietary-related initiatives from its long-term national strategies concerning the targeted 80% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. In other words, Japanese opinion leaders seem to challenge the generally accepted viewpoint of a direct positive correlation between a sustainable diet and a healthy diet, contradicting widely accepted European studies and initiatives (e.g. Sjörs et al. 2017). This apparent controversial observation motivated me to look into the historical development of meat consumption on a global scale. Most importantly, the recently published guiding principles by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019 state that “Sustainable Healthy Diets” are a trade-off between the two dimensions: sustainability and healthiness of diets. Thus, countries should decide on such trade-offs in consideration with their situation and goals (FAO & WHO, 2019).

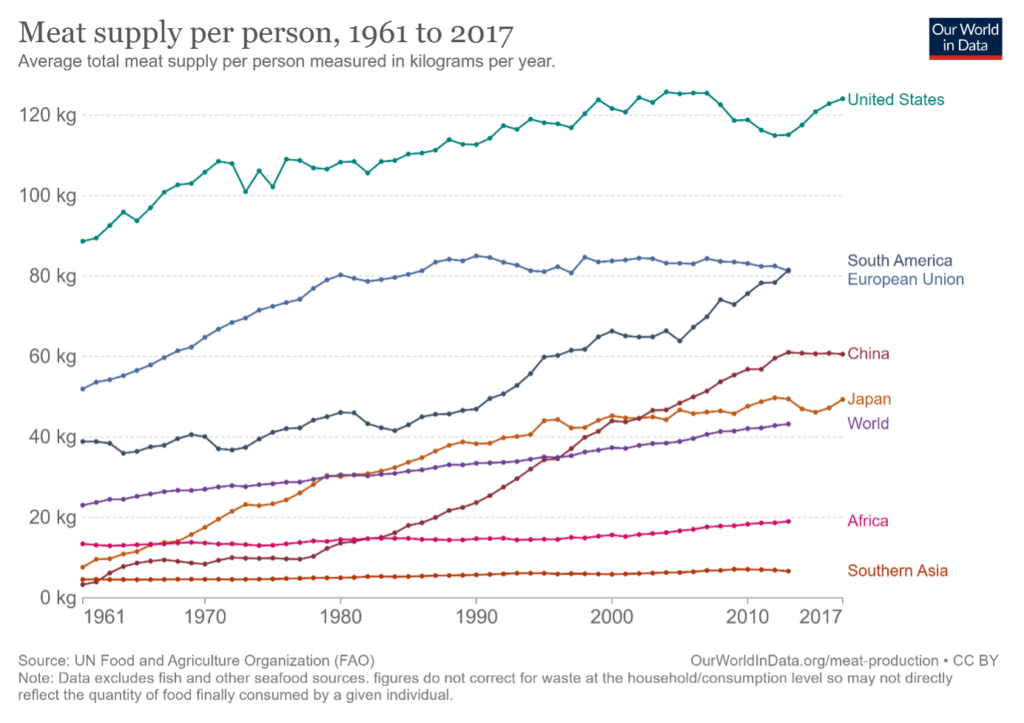

The following figure indicates such a trade-off situation for various geographical regions and it clearly shows that the meat consumption in Western countries is obviously higher than the rest of the world such as compared to e.g., Africa or Asia, although a substantial increase of meat consumption is observed in both China and Japan.

In particular, the main increases observed in China and Japan seem to be well-synchronized with the periods of their respective economic developments that simultaneously triggered their modernization (Westernization) process in their markets. However, the curves of Japanese and Chinese meat consumption also show a noticeable difference. Whereas the meat consumption in China has steeply increased since the 1980es, Japan seems to moderate its increase from the early 1990es and ahead, which is most likely explained by their respective economic developments. However, in this blog, I want to supplement these observations with some personal insights on what has happened in Japan during this period through my work experiences in the related industry.

During the Japanese bubble economy in the 1980es to the early 1990es, the Japanese middle class had increasingly wider opportunities to be exposed to the Western food culture due to their Westernization. This somewhat alarmed key Japanese health professionals, nutritionists, food experts and industries who considered a ”Western lifestyle and food culture” as a source of lifestyle-related chronic diseases e.g., diabetes 2 and cardiovascular issues, which would gradually impact Japanese consumers.

This subsequently triggered a countless number of initiatives aimed to nudge a wide range of the population towards a healthier diet. The initiatives were eventually formalized as a Health Promotion Act in 2002 and the Basic Law on “Shokuiku (food and nutrition education)” in 2005 by the Japanese government (MAFF, 2019).

The Shokuiku act has since become a comprehensive program targeting everyone from school children to the elderly, and its initiatives have involved a broad range of Japanese stakeholders, not only the central and local governments, health professionals and nutritionists but also food and restaurant businesses and their consumers.

The Shokuiku program has promoted the nutritional education from a holistic viewpoint and emphasized the importance of enjoying healthy meals from societal and cultural perspectives through various sensory food experiences. As a consumer researcher in the 1990es in one of Japan’s largest high-tech companies producing various kitchen appliances, I also personally participated in a variety of initiatives involving consumer organizations, health professionals, nutritionists and food and restaurant businesses to nudge consumers towards a healthy diet at that time.

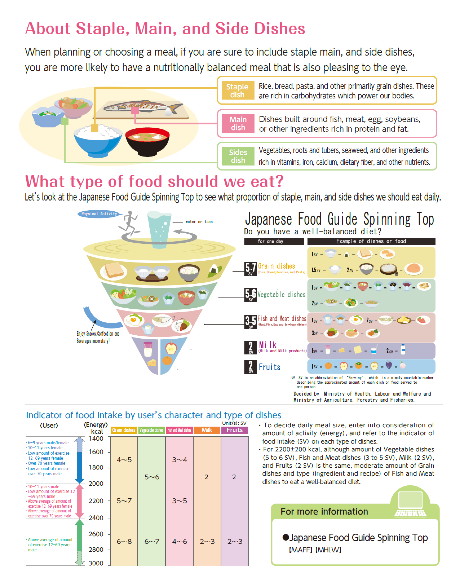

In a European context, nudging consumers towards a sustainable and healthy diet usually implies the replacement of an animal-based diet with a plant-based diet with emphasis on ingredients. One major difference to the Japanese nudging initiatives is that the Shokuiku promotion has encouraged consumers to learn how to select “nutritionally balanced meals” in their daily life while enjoying variations in sensory food experiences. Consumers have many ways to achieve this by following the “Japanese food guide spinning top” that can be easily followed by a wide range of population groups, i.e. from school children to the elderly (see the below picture). The maintenance of a moderate meat consumption level observed from the Japanese curve in the above figure might be partially attributed to such ‘enjoyable’ Shokuiku initiatives (see Yoneda, 2019).

Japan has been able to moderate its overall meat consumption without specific promotions of plant-based diets also thanks to the traditional Japanese food culture that is originally rooted in a plant-rich diet. Thus, in a Japanese context, it is perceived possible to achieve a well-balanced diet while simultaneously enjoying variations in sensory food experiences, in other words, nudging a healthy diet can be perceived as an enjoyable experience. Interestingly, Kanemoto et al. (2019) recently reported that meat consumption only weakly explains the difference between high- and low food carbon footprints (FCF) among 60,000 Japanese households. This study ponders that Japanese should (also) consider restricting their consumption in other areas than meat consumption with a higher estimated FCF such as restaurant foods, confectionary and alcohol.

These observed trends indicate the importance of fully understanding social, cultural and dietary contexts in various countries and regions when researching on sustainable food consumption because food is inherently deeply rooted in the specific cultures. In other words, sustainable consumption studies should ideally shed more light on an emic approach addressing a specific sample of that region and discuss adaptability of such studies to countries outside of the specific region with due respect of the embedded cultural contexts.

About the Author:

Fumiko Kano Glückstad is Associate Professor of Cross-Cultural Cognition at the Copenhagen Business School. She works in the area of cross-cultural psychology and her recent project “iBeauty” funded by the third largest Japanese cosmetic company investigates associations between personal values, beauty and well-being in cross-cultural contexts. She previously worked as a consumer researcher and product concept designer of kitchen appliances at Panasonic Corporation, one of the largest Japanese electronics industry enterprises.