By Kristian Roed Nielsen.

How does crowdfunding look like in Denmark and where is it heading? Drawing on empirical data from two well-known reward-based crowdfunding platforms (Kickstarter and IndieGoGo), I try to give a quick overview of the two most famous examples of crowdfunding in Denmark. After which I will give my predictions for where the Danish crowdfunding sector will head and how the emergence of lending-based platforms like Coop Crowdfunding could help take crowdfunding into mainstream in Denmark. Doing so by tapping into our cooperative movement roots by allowing customers to decide, through their loans, what we will eat in the future.

The bank, they don’t understand shit now, especially not in my business.

An entrepreneur’s view on banks (Junge & Bech, 2019)

Trust in banks is for many good reasons at an all-time low as consequence of a series of damning money-laundering scandals, the facilitations of offshore tax havens for the super-rich (i.e. Panama Papers), and not least the lingering resentments from the 2007 financial crisis. Despite these and other indictments, the sector as whole has seemed remarkably unaffected, perhaps because despite our moral reservations they hold a near monopoly on the purse strings not least when seeking a loan for an entrepreneurial endeavor. Or at least they used to.

The emergence of crowdfunding as an alternative source of finance for entrepreneurs is increasingly challenging the banks near monopoly as entrepreneurs now are increasingly engaging consumers and citizens directly for financial support. Citizens have thus become increasingly common enablers of product and service innovation in their own right (Belleflamme et al. 2014) and the global value of funds raised through crowdfunding have already hit US$ 32 billion in 2017 with continued strong growth expected (Statista 2018).

In Danish context, where loans for SMEs remains restrictive (Nielsen 2019), crowdfunding nonetheless remains a uncommon practice and is generally outside the awareness of many entrepreneurs and consumers (Junge & Bech 2019). This is arguably somewhat surprising given the historic strength of cooperatives in Denmark that were driven forth in part due to strong consumer engagement in businesses. The question then is what is the current state of crowdfunding in Denmark? Drawing on empirical data from respectively Kickstarter and IndieGoGo – the two arguably best known examples of crowdfunding – I have sought to provide you with a quick overview of reward-based crowdfunding in Denmark. After which I will give my predictions for where the Danish crowdfunding sector will head.

Crowdfunding in Denmark: A Quick Overview

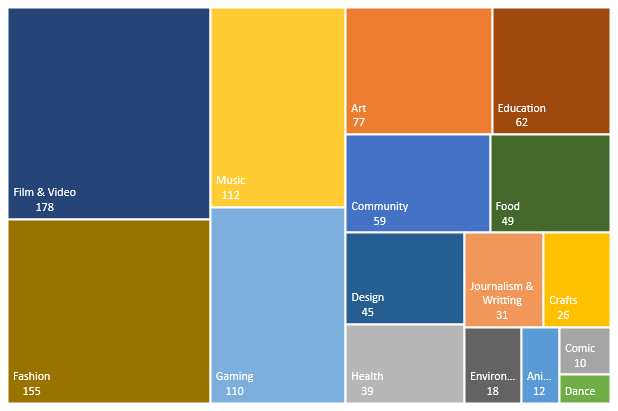

Reward-based crowdfunding emerged as means to finance creative endeavors, which is also apparent when we look into which campaign categories that are most popular amongst Danish founders (i.e. Film, Fashion and Music).

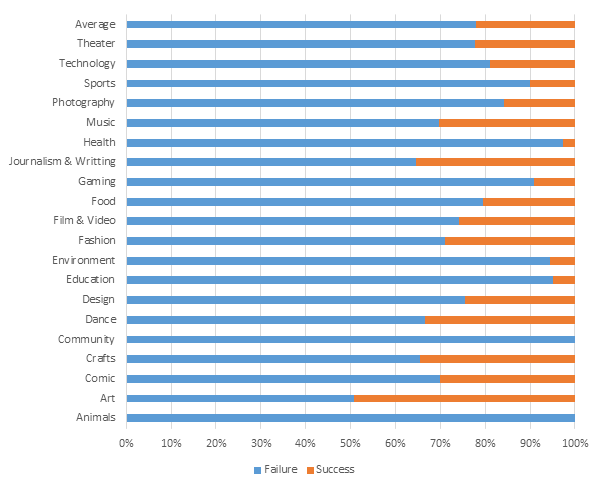

Among these projects, about 22 pct. succeed in meeting their funding goal, while 78 pct. fail to hit their target[1]. However as is illustrated in the Figure 2 these rates vary significantly depending on for example the project category. For example, the project category ‘Art’ is nearly a 50/50 proposition, but campaign categories like ‘Animals’ have a 100-pct. failure rate.

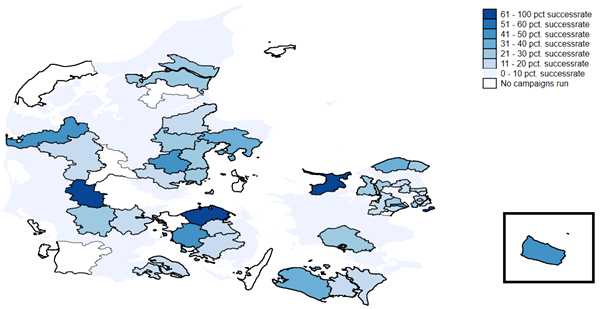

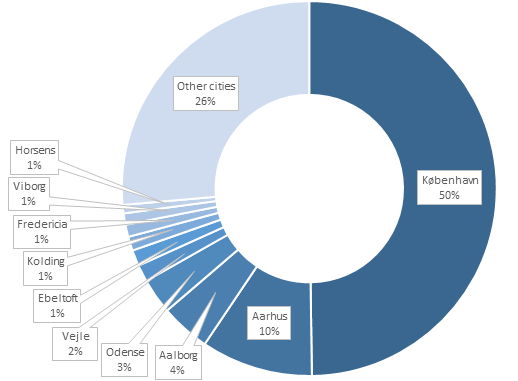

Finally, as illustrated in Figure 3 and 4 respectively success rates are strongly affected by geographic location and the regional distribution of crowdfunding resources thus remains strongly tied to the major cities. For example, Copenhagen alone accounts for 50 percent of resources garnered via reward-based crowdfunding. To see why please read my other recent blog post on this topic. So, while certain municipalities outside the major cities have high success rates one should not assume that they have many successful campaigns. In fact, the two municipalities (Vallekilde and Morud) with a 100-pct. success rate have only one campaign per respective municipality.

Future of crowdfunding in Denmark

Crowdfunding in Denmark remains a rare source of income for entrepreneurs and is generally challenged by a lack of awareness from both entrepreneurs and citizens. This lack of awareness furthermore results in a lack of trust in this new form of financing. However, while reward-based crowdfunding remains niche and tailored to specific entrepreneurial endeavors that can offer tangible perks for their supporters, the emergence of other crowdfunding models provides an arguable basis for a strong competitor to the banks. For example, lending-based models, exemplified by Lendino and Coop Crowdfunding, provide entrepreneurs with an access to loans from their customers (and others) that are often cheaper then what banks are willing to offer (Junge & Bech 2019). The lenders on the other hand, who face little incentive to keep their saving in a fixed interest account at a negligible interest level, are increasingly incentivized to look for alternatives like these lending-based models especially as many loans are guaranteed.

I therefore believe that especially Coop Crowdfunding’s focus on driving new and more sustainable business models within the food sector represents, as they say themselves, a return to a type of cooperative movement 2.0 that is well-placed in Danish context. Coop Crowdfunding provides a platform for entrepreneurs to find engaged citizens who want to drive new and more sustainable food practices and are willing to put their money where their mouth is by offering cheaper loans as compared to the banks. In a country with high levels of trust and in context of an engaging story were consumers themselves can decide what we will eat in the future, I believe Coop Crowdfunding model could signal an opportunity for crowdfunding and not least green growth in Denmark.

Footnote

[1] It is important to bear in mind that there are some significant differences between the two platforms analyzed. While Kickstarter is an “all-or-nothing” platform, which means that the creator of the campaign only keeps the money if (s)he hits their funding goal IndieGoGo is primarily a “keep-it-all” platform, where the creator of the campaign can choose to keep the money if (s)he thinks that they can provide the promised service or product for the money raised. This translates into significantly different “success rates” for respectively IndieGoGo and Kickstarter if hitting the creators funding mark is definition of this. Whereas on Kickstarter 46,4 pct. of Danish campaigns hit their funding goals only 5 pct. do so on IndieGoGo.

References

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T. & Schwienbacher, A., 2014. Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), pp.585–609. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883902613000694.

Junge, I.C. & Bech, L.L., 2019. Choosing Crowdfunding: A study of why entrepreneurs choose to engage in crowdfunding and how the choice of crowdfunding model and purpose change throughout the startup life cycle. Copenhagen Business School.

Nielsen, B., 2019. 10 år efter finanskrisen: Mange små virksomheder får stadig et nej i banken. Jyllands-Posten. Available at: https://finans.dk/erhverv/ECE11308747/10-aar-efter-finanskrisen-mange-smaa-virksomheder-faar-stadig-et-nej-i-banken/?ctxref=ext.

Statista, 2018. Crowdfunding – Statistics & Facts. Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/topics/1283/crowdfunding/ [Accessed April 24, 2018].

About the author

Kristian is Assistant Professor at the Department of Management, Society and Communication and Visiting Researcher at Mistra Center for Sustainable Markets – Stockholm School of Economics. His research explores the potential role that “the crowd” could play in enabling sustainable entrepreneurship and innovation. Follow him on Twitter @RoedNielsen.

By the same author

Photo

Photo by Rob Curran on Unsplash.