By Marco Morazzoni and Dr. Kristjan Jespersen

◦ 8 min read ◦

The impending climate crisis emphasizes the need to mobilize large-scale investments to finance the transition towards a more sustainable and inclusive economy. The financial sector plays a pivotal role in this context, as it allocates capital from investors who wish to pursue financial and non-financial objectives to corporations and stakeholders who need these resources to empower the sustainability transition.

Over the past decades, individual investors have become aware of the risks inherent in unsustainable business practices, being increasingly interested in financial products that combine a competitive risk-adjusted return with Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria. Despite the increase in funds, indices and benchmarks that include ESG dimensions, the universe of ESG financial products remains difficult to navigate for individual investors due to the range of investment strategies that can be used to pursue ESG goals, such as negative and positive screening, best-in-class, ESG integration, impact investing and ESG engagement. In addition to ESG strategic considerations, investors ought to consider the level of active management inherent in their ESG products, since it has considerable implications for financial returns and the ESG objectives pursued.

In fact, while some financial products have an active investment approach, trying to beat a reference benchmark, others merely aim to replicate the ESG impact and financial performance of an index.

‘Active versus passive’ debate

The literature on conventional active and passive investing is almost unanimously in favour of long-term passive investing, due to active managers’ inability to consistently beat the market and to the lower fees charged by passive funds. However, the ‘active versus passive’ debate in the context of ESG investing is more nuanced. This is because ESG investing entails the pursuit of intangible and hardly quantifiable goals that go beyond the achievement of mere financial returns. Furthermore, due to the different definitions and methodologies used in the assessment of ESG performance and the resulting unrealiablity of ESG data, the trade-off between impact and financial returns can be difficult to reconcile.

A study conducted on 78 ESG active mutual funds and 15 ESG exchange-traded funds (ETFs) seeks to contribute to the debate by illuminating the financial and non-financial features that characterize these sustainable financial products. The funds were selected from Morningstar Direct according to specific criteria, such as: availability of an ESG rating, European domicile, invested in equity, active investment approach (for mutual funds) and passive investment approach (for ETFs).

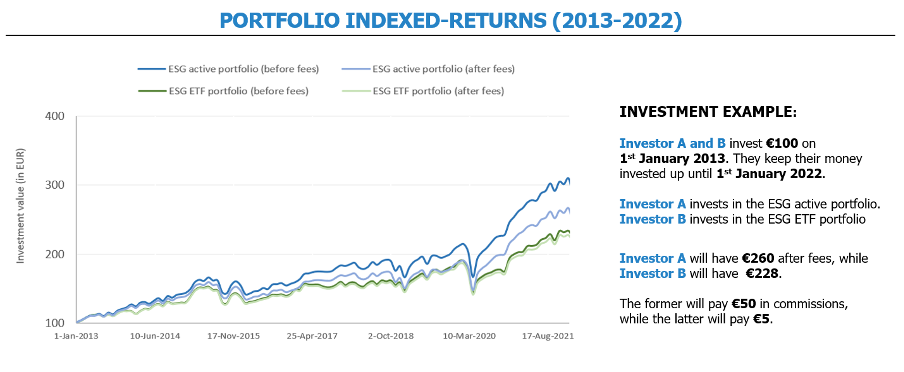

By constructing an equally-weighted portfolio for the selected ESG active mutual funds and ESG ETFs, the study used the CAPM, three-factor, four-factor and five-factor model to compare the portfolios’ risk-adjusted perfromance before and after fees. To increase the robustness of the study, the regression analysis was conducted on various market benchmarks, such as MSCI World, STOXX Europe 600, MSCI World ESG Leaders and MSCI Europe ESG Leaders.

The regression results indicated that the ESG active portfolio outperformed the ESG passive portfolio both before and after accounting for management fees. Controlling for the criteria used in the selection of the funds, the active outperformance could be attributed to the funds’ instrinsic characteristics, such as investment orientation, ESG investment approach and ESG scores. Accordingly, 77% of the ESG active portoflio had a global investment orientation compared to 27% of the ESG ETF portfolio. This entails that the active portolio covered more geographies, exhibiting higher diversification and improved risk-mitigation.

Further, 83% of the active portfolio practiced ESG engagment, a strategy that previous literature associates to superior financial returns and improved ESG impact.

By engaging with companies on ESG issues, ESG active funds may have been able to help ‘lagging’ firms improve their ESG performance, while enabling ‘leading’ firms to address their ESG issues. With respect to ESG scores (Morningstar and MSCI), the active portfolio displayed a lower overall ESG score compared to the ESG ETF portfolio. This finding could suggest that the active portfolio invested in lower rated companies on average, with the objective of helping them transform their ESG strategy and thus pursue higher risk-adjusted returns.

Insights to individual investors in ESG financial products

Recognizing the limitation derived from the small sample size and the fact that the active outperformance might be due to the specific funds selected, the findings were used to provide a set of insights to individual investors who wish to invest in ESG financial products.

Firstly, individual investors were categorised into ESG-unaware, ESG-aware and ESG-motivated, according to the investor labels used by Pedersen et al. (2021) “Responsible investing: The ESG-efficient frontier”. This categorization simplified reality to the extent that it became easier to derive actionable insights. Furthermore, it provided more granularity with respect to investors’ prerogatives regarding the trade-off between the pursuit of an ESG impact versus a risk-adjusted return.

Based on this categorization, investors who disregard ESG information (ESG-unaware) should invest passively in broad conventional ETFs or in a diversified portfolio of more specific conventional ETFs.

Investors who consider ESG information for risk-mitigation purposes (ESG-aware) ought to focus on the level of selectivity displayed by active managers in their stock-picking activity, measured in terms of high/low R-squared. If active managers are highly selective (low R-squared), ESG-aware investors may consider foregoing part of their return, due to the higher active management fees, and thus benefit from managers’ ability to pursue a greater ESG impact and potentially higher risk-adjusted returns.

Conversely, if active managers exhibit low selectivity with respect to a reference benchmark (high R-squared), investors would be better off investing passively in broad ESG ETFs or in a diversified portfolio of more specific ESG ETFs. Lastly, ESG-motivated investors may be better off investing in ESG active funds who practice ESG engagement, as the higher fees charged by these funds would worthwhile, given the superior ESG impact inherent in ESG engagment strategies.

Regulatory considerations

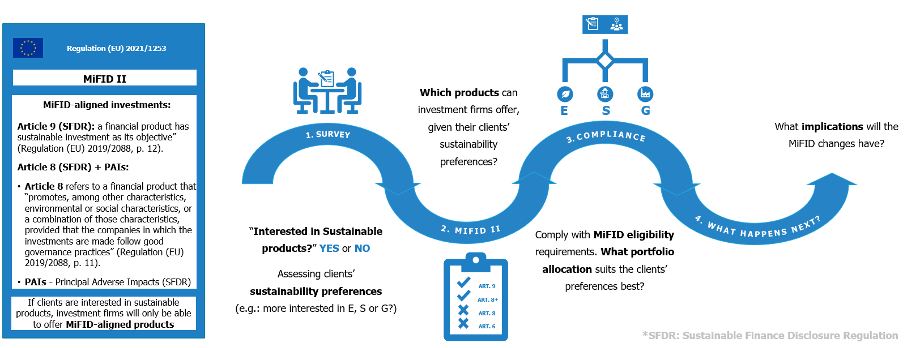

In addition to the empirical findings, the study also included regulatory considerations in the assessment of the suitability of active versus passive ESG financial products for individual investors. This was critical, since the new MiFID for sustainability preferences will come into force on the 2nd of August 2022.

According to this regulation (2021/1253), investment firms will be obliged to ask their clients about their sustainability preferences and find out whether they are interested in sustainable financial products. If the answer is affirmative, financial advisors will only be allowed to offer MiFID-aligned products to their clients. A MiFID-aligned product will have to include a minimum portion of ‘environmentally sustainable Investments’ (SFDR article 9), EU Taxonomy-aligned investments, or enhanced article 8 investments, consisting of article 8 investments (SFDR article 8) which also include Principal Adverse Impact (PAI) indicators.

Linking the new regulatory requirements to the findings of this empirical research, it is reasonable to expect that ESG-unaware investors will no longer exist, as investment firms will be legally required to inform these clients about the ESG implications inherent in their investments. This will give rise to an increase in supply of sustainable financial products (MiFID-aligned), as investment firms strive to keep up with the increased demand for these products. The rise in supply will most likely be larger than the increase in demand, since a portion of the new ESG-aware investors might continue disregarding ESG information, if ESG financial products are priced unreasonably (excessively high management fees). This will ultimately lead to higher competition among investment firms, with a consequent downward pressure on fees in the long-run. Lower investment costs could subvert individual investors’ incentives, as they decide on whether to invest in ESG active or passive funds. Accordingly, it might become desirable for ESG-aware investors to invest in ESG active funds who practice ESG engagement, as opposed to it being a strategy exclusively suitable for ESG-motivated investors.

The information contained in this blog post is not to be taken as constituting the giving of investment advice or recommendation. The reader is acting for its own account, and they will make their own independent decisions as to whether any investment is appropriate based upon their own judgment.

About the Author

Marco Morazzoni is a recent graduate in MSc Applied Economics and Finance from Copenhagen Business School. Having an interest in finance and ESG, he wrote his master’s thesis on “ESG exchange-traded funds versus ESG active funds: how can individual investors pursue ESG objectives while achieving competitive risk-adjusted returns?”

Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies on the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.

Photo: Khanchit Khirisutchalual on iStock