By Milena Bar, Ottilia Henningsson, & Dr. Kristjan Jespersen

◦ 5 min read ◦

The Science-Based Targets initiative aligns firms’ emission reduction targets with a net-zero emissions pathway. Firm commitment yields significant abnormal returns which are larger for firms committed to larger emission reductions and for high-emitting firms.

The IPCC’s sixth assessment established a code red for humanity and provided mounting evidence of widespread, rapid, and intensifying climate change. The Paris Agreement, ratified by over 190 states and non-state actors in 2015, formally stipulated the goals of limiting global warming to ideally 1.5°C and at a minimum well below 2°C with the aim of reducing the most catastrophic damages related to climate change onto the natural environment, human health and global financial market. The need for climate action is urgent and requires engagement from governments, individuals as well as corporate and investor participation.

Combatting climate change requires voluntary private sector engagement

Incentivizing corporations and investors to act voluntarily on climate change is critical to redirect private capital towards environmentally responsible business practices. The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) is becoming the global standard for firms seeking to set emission reduction targets aligned with the required global decarbonization targets established in the Paris Agreement. By encouraging voluntary corporate carbon emission reductions, the SBTi is a critical tool to reduce the private sector’s reliance on fossil fuels.

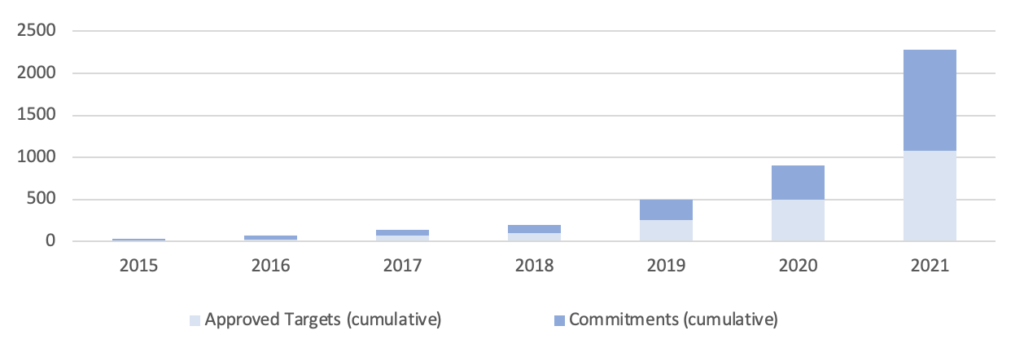

2021 record year for new approved targets and committing firms for SBTi

Since its founding, just seven years ago, SBTi has experienced exponential growth in the number of committing firms and has mobilized firms representing more than a third of global market capitalization to reduce their carbon emissions. In 2021 the initiative took steps to increase the ambition level of firms’ emission reduction targets. When first established, firms could commit to reduce their emissions either aligned with the reduction targets of 1.5°C or 2°C. However, from summer 2022, the initiative will only be accepting the more ambitious emission reduction target, as set out in their campaign Business Ambition for 1.5°C.

Since company engagement ultimately comes down to whether committing to SBTi will drive wealth for shareholders, understanding the stock market response to firm commitment to the SBTi is essential not only for businesses looking to commit, but also for investors. To justify the integration of a climate credential such as the SBTi in investment management, it needs to be able to provide excess returns. To understand the stock market reaction to firms’ announcement of SBTi commitment, we conducted a short-horizon event study on a portfolio of 1.535 firms.

Firm commitment to the Science Based Targets initiative aligns environmentally sound practices with financial viability

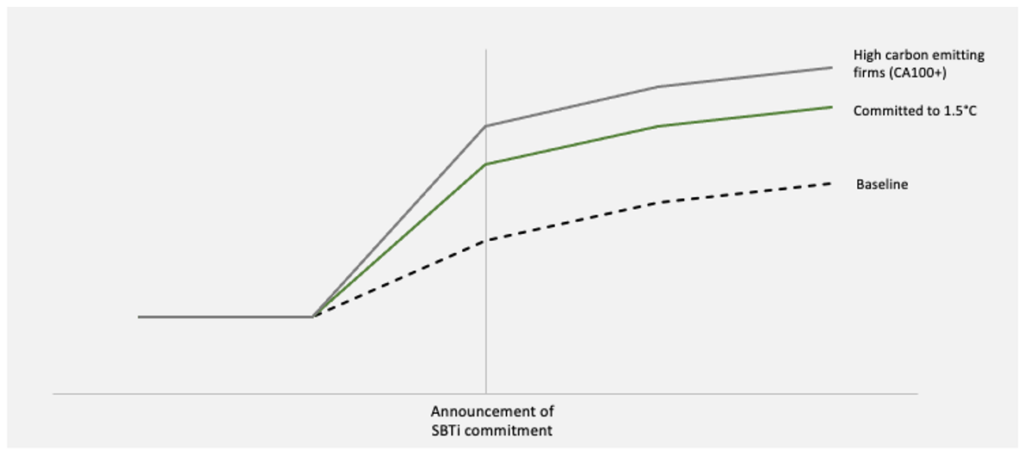

Firm commitment to the SBTi indeed yields a positive announcement abnormal return and thus speaks to the credibility of SBTi in constituting a credible signal of firm commitment to sustainable business practices. Even more encouraging is the finding that firms committed to the 1.5°C target experienced substantially higher returns, indicating a stronger positive market reaction when exhibiting a higher cost of commitment and higher target ambition level. The market evidently differentiates between ambition levels by rewarding businesses that are pledging themselves to more demanding emission reductions and a more climate-friendly business strategy. These findings are particularly relevant in light of the SBTi making the more stringent emission reduction target the new standard for all firms via their campaign Business Ambition for 1.5°C and may encourage more firms to increase their efforts in reducing their greenhouse gas emissions.

Stock price reaction in response to commitment to the Science Based Target initiative

In turn, high carbon emitting firms, proxied here by firms identified by the CA100+ list, reaped the largest reward in their stock price following commitment. This finding further confirms the market’s more sensitive reaction to costlier commitments, but also creates concern about whether the SBTi may have to rethink a recent strategic decision. The SBTi announced that they will not be accepting targets set by firms operating in the Oil and Gas industry, thus abandoning the industry specific methodology for fossil fuel firms which had been in development for several years. Fossil fuel firms have a key role to play in successfully achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement, thus begging the question of whether the SBTi is not missing out on covering an industry critical to combatting climate change and a sector of firms who are highly rewarded by the market for committing to reduce their emissions.

As climate disasters become more prevalent and more severe, firms who fail to transition to a low, or zero, carbon business model can be expected to become more vulnerable in the long run. To expand the analysis, we further tested the performance of a portfolio strategy screened for firms committed to the SBTi. Despite the underperformance of an SBTi screened portfolio against a portfolio consisting of only non-committed firms in the medium-term, there is reason to believe that a portfolio with SBTi committed firms may provide higher returns in the future. Given that SBTi commitment represents a commitment to aligning the firm’s operations with the net-zero emissions pathway, it can be perceived as a safer bet in the long run. Moreover, portfolios consisting of SBTi firms were shown to be characterized by lower volatility. The objective of investors is shifting to increasingly sustainable and impact focused investment profiles, hence portfolio and asset managers may use SBTi commitment as a filter in security selection to achieve their client’s demand.

Looking Ahead

Financial institutions have a key role to play in driving systematic economic transformation towards a global net-zero carbon emissions economy in their power to lend and invest. As evidenced, firm commitment, ambition level and cost of commitment are reflected in the stock’s pricing mechanism, making the business case for the firm to set ambitious targets for decarbonization, and providing rationale for investors to in the short run utilize the market’s reaction to firm commitment in investment processes and strategies.

About the Authors

Milena Bär is a recent graduate in MSc Applied Economics and Finance and is working as a student researcher in ESG and Sustainable Investments at Copenhagen Business School. Her research projects are mainly within the field of ESG metrics and regulation, with a focus on the investor’s side.

Ottilia Henningsson recently graduated with a MSc in Applied Economics and Finance from Copenhagen Business School with a keen interest in the transition towards a more sustainable financial industry.

Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies on the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.

Photo by Matthias Heyde on Unsplash