By Nina Böntgen, Sara Derse and Meike Janssen

◦ 4 min read ◦

The fashion industry has repeatedly come under fire for its negative effects on the environment. With heightened attention towards the climate crisis and scandals highlighting the industry’s social shortcomings (Rana Plaza, 2013), more and more ‘native’ sustainable fashion brands have emerged. However, parallel, we witness a trend towards ever-increasing consumerism. Frequently, Black Friday is seen as the epitome of consumerism which raises the question: How do sustainable fashion brands approach the biggest shopping day of the year – Black Friday – and how do consumers perceive these campaigns?

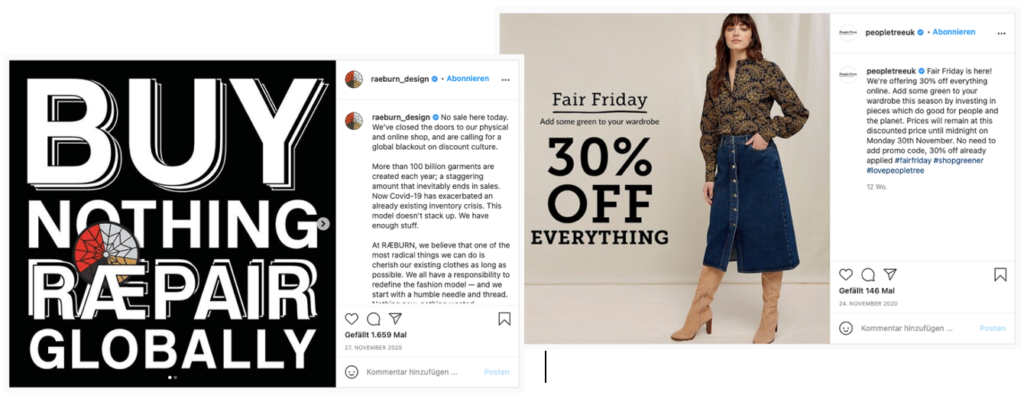

We reviewed Black Friday Instagram posts by self-claimed sustainable fashion labels and found they can be conceptualized along two axes: (1) the level to which consumption is encouraged / discouraged, and (2) the degree of action taken by a brand to express its commitment to sustainability. This conceptualization accounts for existing societal marketing strategies, particularly Demarketing, Green Marketing, and Cause-related Marketing. On the one hand, the brand Raeburn closes its shops and urges consumers to use Black Friday to repair their clothing rather than buying new items (Demarketing). On the other hand, the brand People Tree promotes 30% off everything claiming that consumers should “add some green to [their] wardrobe” (Green Marketing).

Business-as-usual, a revolution, or planet-saving purchases – what is actually authentic?

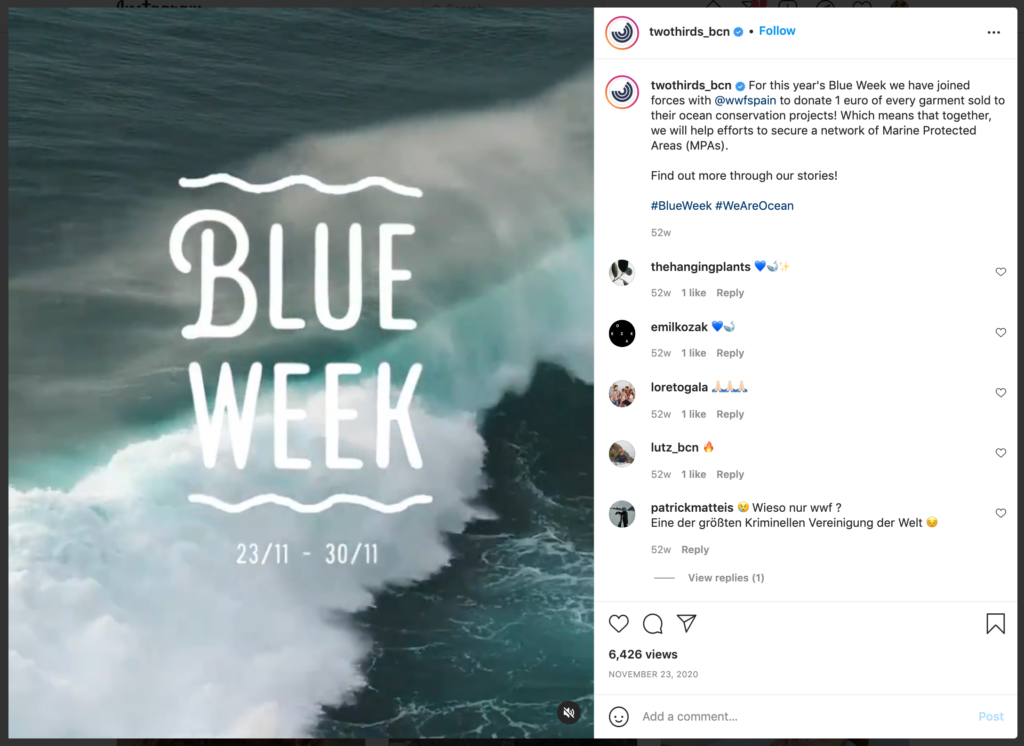

By interviewing 20 consumers, we found that they judge authenticity by inspecting various cues that are leveraged to identify authenticity drivers. For example, donating to WWF (Cause-related Marketing) yielded legitimacy for TwoThirds’ Black Friday campaign. Authenticity is a complex concept – it is multidimensional, subjective, dynamic and socially constructed. Multidimensionality implies that one cannot answer “what is authentic?” precisely; it is an interplay of different attributes. In our case, respondents described an advertisement as authentic when it was credible, relatable, congruent, original and/or impactful. Next, subjectivity means that what is authentic for one person is not necessarily authentic for another. Influential consumer characteristics are a person’s general scepticism towards advertising, level of environmental concern, and understanding of sustainability, resp. do we simply need less- or better/greener consumption to mitigate climate change?

“and it’s kind of a contradiction: ‘Please shop to help the planet’ and I think you can’t shop and help the planet at the same time. So less or no consumption is at all times the best option” (Consumer 1)

“you’re using capitalism to make the world a little bit better. And I think in my eyes, that’s a good strategy to go for” (Consumer 2)

Third, authenticity perceptions can change over time, for example upon new information. Last, authenticity does not exist as a stand-alone concept but is always sensitive to societal changes.

What does this imply for marketers of sustainable brands?

Black Friday is a dynamic context in which brands have to actively reflect on their communication strategy and respective consumer authenticity perceptions. Consequently, no communication strategy shows clear advantages or can be labeled ‘most authentic’. We advise brands to reflect on:

- Their standpoint regarding Black Friday

- The needs of their target group

- The statement they want to make on Black Friday

- The tone they want to adopt in their campaign

Sustainable brands increasingly embrace creative ways to distance themselves from the traditional Black Friday, e.g. by closing shops, ‘selling rubbish’ or even raising prices. It remains unclear, however, whether these forms of brand activism reflect a brand’s honest opinion or are employed as a tool to stand out.

We also observe brands who are holding their customers responsible: on Black Friday 2020, Armed Angels let buyers choose between a higher discount or rainforest protection. After Black Friday, the brand revealed that the majority of their customers had chosen the higher discount, which raises the question:

Can consumers be held responsible for making more mindful purchase decisions or is increased action by companies and governments needed?

Upon stating its disappointment about the outcome, followers accused the brand of shaming their customers for choosing higher discounts. This translates to another relevant consideration for sustainable fashion labels – choosing the right tone. While radical messaging conveys urgency and appeals to environmentally concerned consumers, others feel opposed to it and, instead, want to be involved in dialogues. Again, this shows that when it comes to Black Friday, there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution – rather, brands should take time to think about their values and how they can make a meaningful difference on Black Friday 2021.

Throughout the interviews in our study, multiple consumers shared with us how they were inspired by campaigns of sustainable brands and respectively questioned their purchase decisions. This demonstrates that sustainable brands’ communications can actually exceed Black Friday and have lasting effects – not only on their brands’ perceived authenticity but also on our planet’s future.

About the Authors

Nina Böntgen is a recent graduate from MSc Brand and Communications Management program at Copenhagen Business School. Next to her studies, she was actively engaged as team lead and board member of oikos Copenhagen, a student initiative driving change towards greater sustainability. She’s happy to share further insights or engage in discussions on the post or the broader thesis (how sustainable brands navigate authenticity and greenwashing) via email (n.boentgen@web.de) or Linkedin.

Sara Derse is a recent graduate of the Msc Brand and Communications Management program at Copenhagen Business School. Fascinated by the topics of consumer psychology and purpose branding, she was involved in the sustainability-focused student initiative oikos as a Project Manager. She is happy to discuss her thesis (consumer perceptions of fashion brands with a purpose centred around sustainability) in further detail via email (saraderse@live.de) or Linkedin.

Meike Janssen is Associate Professor for Sustainable Consumption and Behavioural Studies, CBS Sustainability, Copenhagen Business School. Her research focuses on consumer behaviour in the field of sustainable consumption, in particular on consumers’ decision-making processes related to sustainable products and the drivers of and barriers to sustainable product choices.

Photo by Ashkan Forouzani on Unsplash