How can financial investors better understand underlying risks and act accordingly

By Amanda Wildhaber, Dominik Wingeier, Jessica Brügger, Nico Meier, and Dr. Kristjan Jespersen

◦ 4 min read ◦

Forests play a crucial role in tackling climate change and protecting biodiversity. Around 12 million hectares of tropical forest worldwide were lost in 2018 and approximately 17% of the loss stem from the Amazon alone. The main drivers of deforestations are soy, palm oil, cattle and timber production. As deforestation may harm a company’s reputation, directly affect its supply chains and increase regulatory risks, many institutional investors are concerned about the impact deforestation can have on their portfolio companies.

How can deforestation be measured?

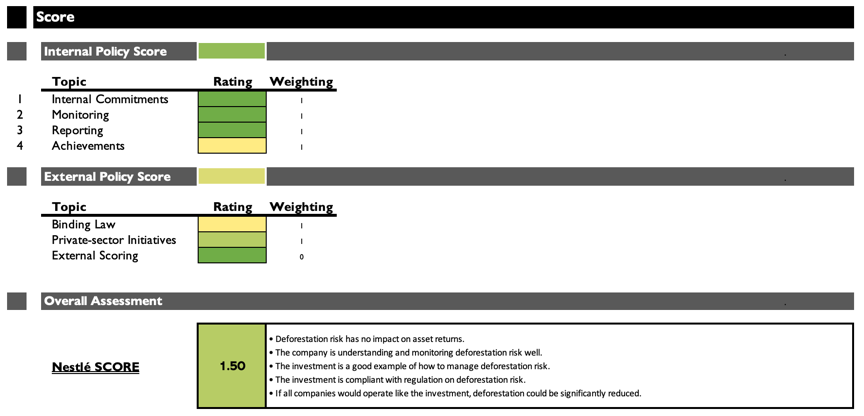

The definition of deforestation risk from an investor’s perspective is difficult to lock-in because different frameworks and approaches focus on different aspects of the risks. The amount of information and the lack of transparency can be overwhelming to financial investors. Therefore, a helpful framework for financial institutions to systematically evaluate the deforestation risk management of portfolio companies has been developed. The framework is divided into two parts, an internal assessment of a company’s commitments and achievements regarding deforestation and an external assessment of outside policies related to deforestation, namely binding laws and private sector initiatives. The framework may serve to complete a scorecard which gives an overview of how well prepared a specific portfolio company is and if it is able to deal with deforestation risks and future regulatory changes. The final scorecard reflects the deforestation risk of financial institution’s portfolio companies.

Is voluntary support sufficient?

Many companies voluntarily support sustainability initiatives and follow zero deforestation commitments (ZDCs) to signal their intention to reduce deforestation associated with the commodities in their supply chain. The reasons behind their commitments include demonstrating corporate social responsibility (CSR), reducing the risk of potential reputational harm and supply chain disruptions. To understand the value of these commitments in mitigating deforestation and associated risks, it is important to critically analyse them in terms of their scope, effectiveness, monitoring and achievements. This includes for example, assessing how companies define deforestation and whether they systematically measure the compliance with their commitments.

External pressure to facilitate internal commitments

It is valuable to see companies implementing robust internal policies and commitments to manage and monitor their deforestation risk. However, it is also important to have external policies in place to hold companies accountable. There are two types of external policies the proposed framework is based on.

- The first type are binding laws which apply for portfolio companies and thus represent a regulatory risk. The EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) of 2010, which prohibits the sale of illegally logged wood in the EU, is one example for such a binding law.

- The second type are initiatives by third parties, which are of a non-binding nature and complement the binding law. One such initiative is the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which is an initiative by private companies as well as external parties targeted to eliminate unsustainable palm oil production.

How do the companies score?

Based on the assessment of the two pillars of the framework – internal and external – a scorecard is derived which assists investors to better understand how a portfolio company or a new potential investment is managing its deforestation risk. Answering questions with scores from 1 to 3, whereby 1 is the best score and 3 the worst, the proposed scorecard allows the quantification of the deforestation risk management of a company. While the distinction between 1, 2 or 3 is not always straightforward, the final score gives a tangible assessment of how well a company is positioned to manage its deforestation risks and associated future regulatory changes. The following scorecard provides an overview of the assessment and indicates how well Nestlé is managing deforestation risks.

Having such a scorecard allows investors to manage and mitigate the deforestation risks they face in their portfolios. In addition, the final scorecard enables investment analysts to directly compare potential investments with other companies and can be used as a parameter in the investment process.

The call for action is getting louder

New regulatory requirements, growing public scrutiny and extended private sector initiatives (such as the investor-led initiative Climate Action 100+), mean that it is becoming increasingly important to properly manage deforestation risks. This is also becoming a key concern for financial investors and it is time to think about systematic approaches on how to include deforestation into the investment process. The proposed framework is intended to serve as a starting point for just that. It allows a quantification of deforestation risk and the identification of critical factors. Building the basis upon which investors can engage with companies. This is a first step to support the mitigating of not only financial but also ecological risks.

About the Authors

Amanda Wildhaber is completing her masters in Economics at the University of St. Gallen. She works as a Junior Consultant in the Strategy team of Implement Consulting. Her interest in ESG and sustainable investments developed when she wrote her bachelor thesis on social enterprises in India.

Dominik Wingeier is studying master’s in Banking and Finance at University of St. Gallen. Dominik has been working for BlackRock where he was responsible for executing and monitoring primary, secondary and direct investments in infrastructure projects.

Jessica Brügger is studying master’s in Business Innovation at the University of St. Gallen. Jessica is currently a board member of the Private Equity & Venture Capital Club of the University of St. Gallen and is particularly interested in making the financial industry more attractive to women.

Nico Meier is studying master’s in Accounting an Finance at the University of St. Gallen. Nico has been working at BLR&Partners where he is responsible for private equity investments. Additionally, he has experience providing M&A, ECM and DCM services.

Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies on the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.

Source: photo by Justus Menke on Unsplash