By Zuzanna Lewandowska and Dr. Kristjan Jespersen

◦ 7 min read ◦

Oil and gas development in the Arctic has long been a subject of controversies, due to the vulnerability and pristineness of the arctic ecosystem, as well as the challenges that the region faces because of climate change. In the light of growing pressure from stakeholders, legislators, and the public, an increasing number of banks, insurers, and investors have been committing to restricting financing of arctic drilling. Typically, this is addressed by formally excluding the funding of oil and gas development in the Arctic from the firm’s investment universe.

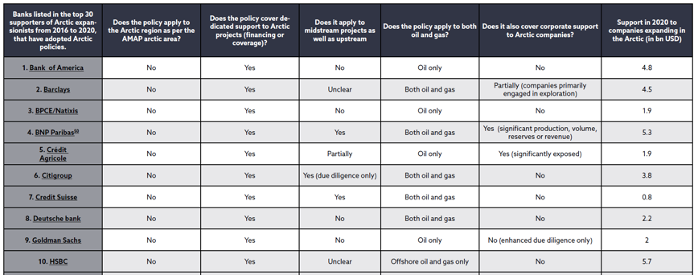

However, several key issues with the current formulations of financial actors’ investment exclusions, make the restrictions potentially ineffective in curbing oil and gas expansion in the Arctic. Firstly, the exclusions typically apply only to financing and coverage, allowing for unrestricted provision of corporate support. Secondly, imprecise financial proxies are used to specify the activity levels at which an exclusion should be applied. For example, exclusions are often based on a revenue threshold, which does not cover early-stage exploration activities that typically do not generate revenue. Lastly, most restriction policies do not refer to a specific definition of the Arctic, which allows for the use of a case-by-case approach when making financing decisions. Where a definition of the Arctic is used, justification is rarely provided for why a specific exclusion zone had been chosen.

Problem 1: How should the Arctic be defined?

Figure 1 below shows the geographic definitions of the Arctic which arctic restriction policies are most commonly based on. It is evident that they differ significantly in terms of scope.

When choosing which definition of the Arctic to use in their exclusions, financial actors are presented with a difficult choice.

Selecting a wide-reaching exclusion zone, such as the arctic region monitored by the Arctic Monitoring Assessment Programme (AMAP), helps ensure that all assets located in the Arctic are covered. This said, however, such broad exclusions place investors at risk of missing out on profitable investments in ambiguous locations such as the Barents Sea, which has been argued to not be significantly different from the Norwegian sea in terms of oil spill response preparedness or ecosystem vulnerability. This dilemma becomes especially relevant in the context of asset managers’ fiduciary duty.

At the same time, if the exclusion is based on a definition of the Arctic which is too narrow, the policy is rendered largely ineffective, as it fails to restrict the financing of arctic oil and gas projects which continue to have negative environmental and social impacts. Which definition of the Arctic should be used as basis of a restriction policy, needs to establish based on a nuanced understanding of the geographic distribution of material issues associated with oil and gas development in the area.

Problem 2: Identifying the negative impacts of arctic drilling

To be able to argue for a targeted exclusion as part of a responsible investment policy, financial actors must credibly prove that the environmental and social impacts of a given activity are particularly dire. Indeed, the discussion is still ongoing as to what extent the documented harmful social and environmental processes in the Arctic can be categorized as by-products of arctic drilling, rather than as cumulative consequences of other activities.

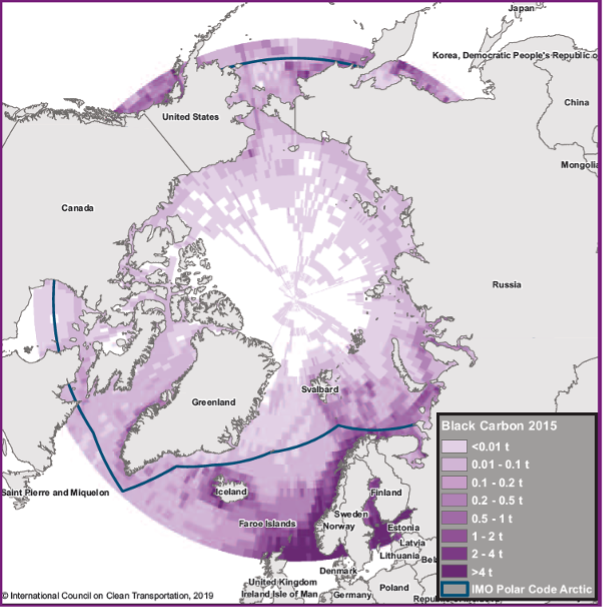

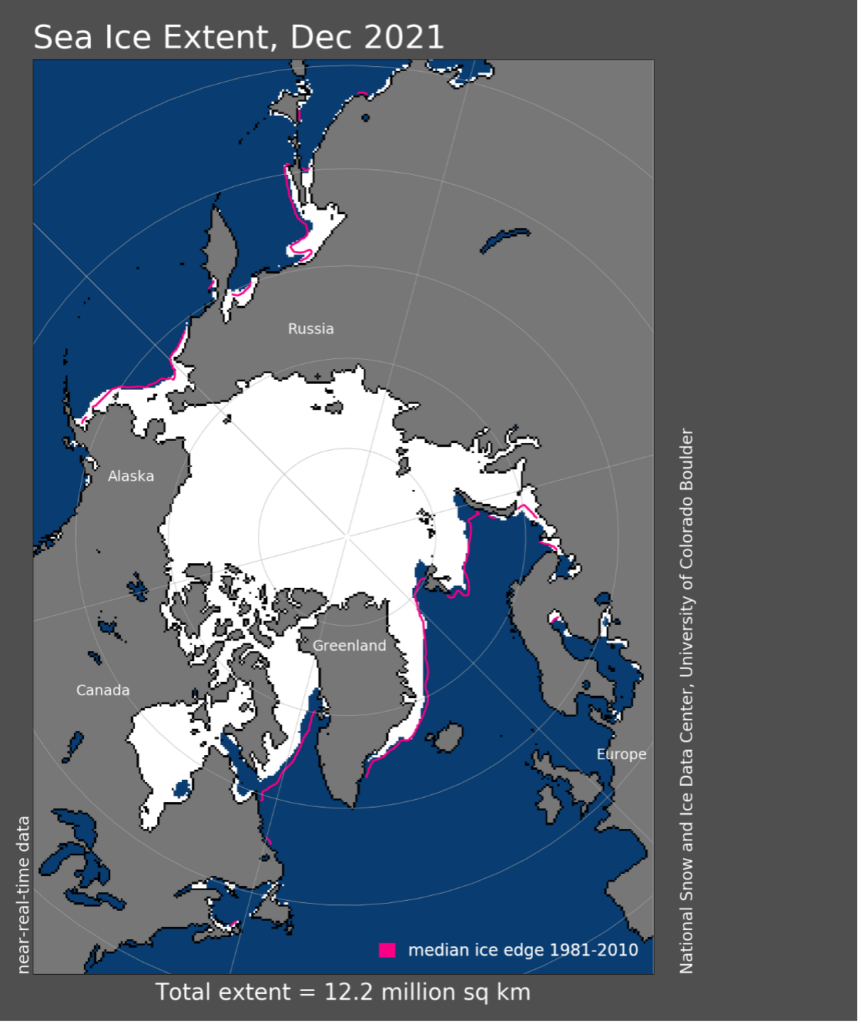

One of the most common environmental concerns regarding arctic drilling is that it contributes to the melting of the polar ice caps. However, research has found that while black carbon emissions from oil and gas exploration in the Arctic reduce the ice cover’s reflective properties, polar caps are primarily melting due to the increases in global temperatures. As such, one could argue that for an exclusion to significantly tackle the issue of polar ice cap melting, it should extend to investments in all fossil fuel developments worldwide.

The negative environmental impacts which have been uniquely linked to arctic drilling (e.g., offshore oil spills, black carbon emissions, and biodiversity threats) are notably difficult to capture within a territorial exclusion zone. This is due to the lack of consistent data on their dynamically changing distribution.

The issue with addressing the negative social impacts of arctic drilling (e.g., land conflicts, threats to food security) in an exclusion policy, is that similar issues are faced by local and indigenous populations in other vulnerable areas, where oil and gas extraction also takes place, and where investments are not subject to restrictions. Here, a notable example would be the Amazon.

An additional complication results from the differing perspectives on arctic oil and gas development, with many local stakeholders crediting it with having improved infrastructure and employment opportunities in the region.

Problem 3: A double materiality perspective – addressing the risks to oil and gas development operations in the Arctic

From a risk management perspective, a comprehensive investment restriction policy should also account for the unique material risks to profitability of oil and gas projects in the Arctic, which make financing and coverage more volatile. This also falls in line with the double materiality approach to impact assessment.

The most significant material risks to oil and gas operations which are distinctive to the Arctic are caused by permafrost thawing, sea ice and icebergs, and extreme weather conditions. Similarly to negative environmental impacts, the dynamic nature of these arctic risk factors makes them difficult to capture within a geographic exclusion zone.

What have we learned?

Based on the discussion of the complexities associated with arctic exclusions, it can be concluded that the weakness of key financial actors’ arctic policies is that they deploy ex ante investment restrictions as standalone policy solutions. Arguably, exclusions can be an effective instrument, but only as part of a comprehensive responsible investment strategy, which covers all stages of the investment process and addresses the extensive information needs regarding material issues.

A well-formulated exclusion can help streamline the pre-investment negative screening process by filtering out investments which:

- Have been proven to be associated with unique material risks and negative impacts,

- Can be identified with high precision, accounting for the dynamic changes and complexities in the underlying material issues.

Those of the material risks and impacts which cannot be captured in an exclusion policy should be addressed using other pre-investment (positive and negative screening, information requests and questionnaires) and post-investment (active ownership and thematic engagements) measures.

Such a nuanced approach to policy exclusions could provide a powerful responsible investment tool for financial actors in areas and sectors which require additional due diligence.

About the Authors

Zuzanna Lewandowska is a student researcher in ESG and Sustainable Investments at Copenhagen Business School. She studies responsible investment strategies and the state of the art of measuring and reporting information on ESG factors. She has a background in international business and strategy, global market intelligence, and policy consulting.

Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies on the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash