By Levinia Scotti and Thomas Eichenberg.

The overconsumption of sugar, especially among children, and its long-term health risks re-gained public awareness with the introduction of the British soda tax in 2018. What can we learn for 2019?

Food and beverage manufacturers and retailers produce, advertise and sell their products to millions of people every day. We therefore consider them political actors (see for a similar argument, Whelan 2017) with a responsibility to respect the Human Rights of Children to a healthy diet (OHCHR 1999).

By using sugar as a proxy for the healthiness of children’s dietary patterns, we sought to learn more about the capabilities of food companies to act in favour of children’s long-term health. Children’s health does not only affect themselves and their families, but also implies important economic spill-over effects (e.g., Brownwell et al. 2009, Belli et al. 2005, Heckman 2006).

The Case

In order to better understand existing corporate efforts, we conducted a number of interviews with representatives of Danish and German retailers as well as international food and beverage manufactures. Additionally, we analysed their annual and sustainability reports of the last five years.

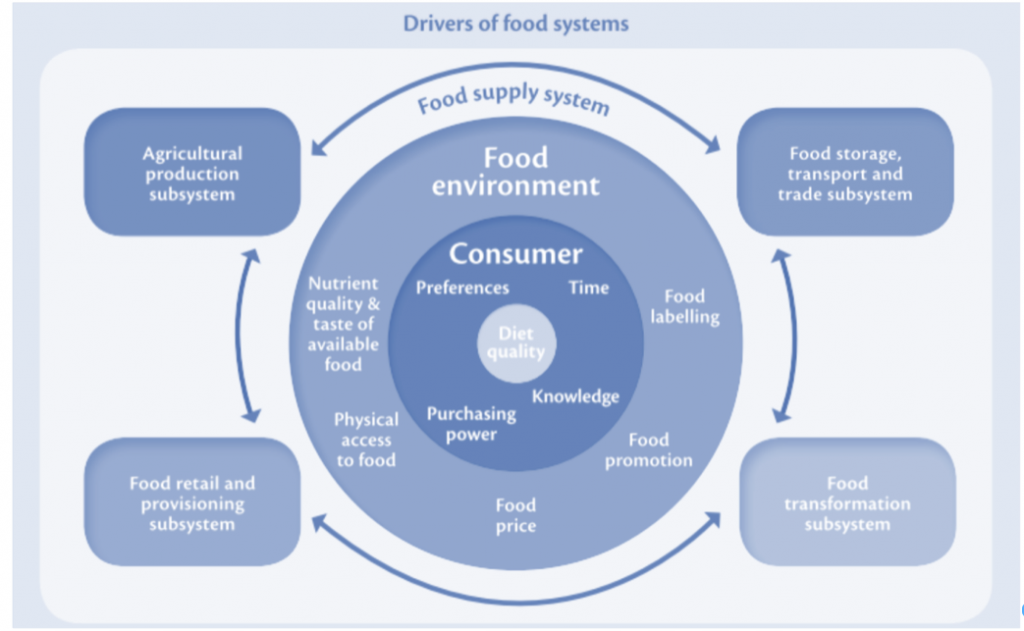

For our analysis, we assumed that individual food choices are contingent on the social and environmental factors that constitute the food system. Dietary patterns and food systems can thereby be seen as a two-way street (GloPan 2016) in as much as consumption choices are being shaped and shape (future) food system configurations. The innovation challenge in improving children’s dietary quality is thus systemic. (See also the Global Nutrition Report 2018 for more on malnutrition).

Corporate Challenge: ‘Sense-Making’, and the Quasi-Objectivity of Materiality

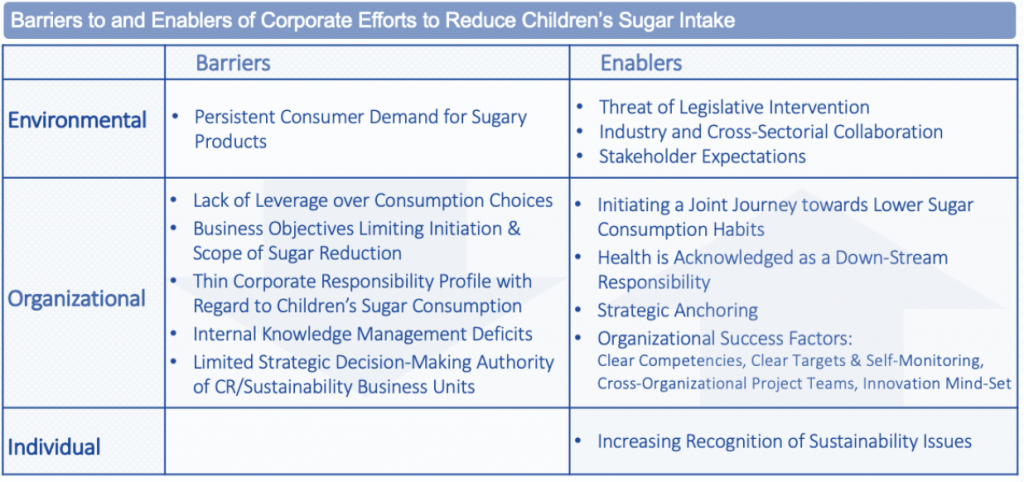

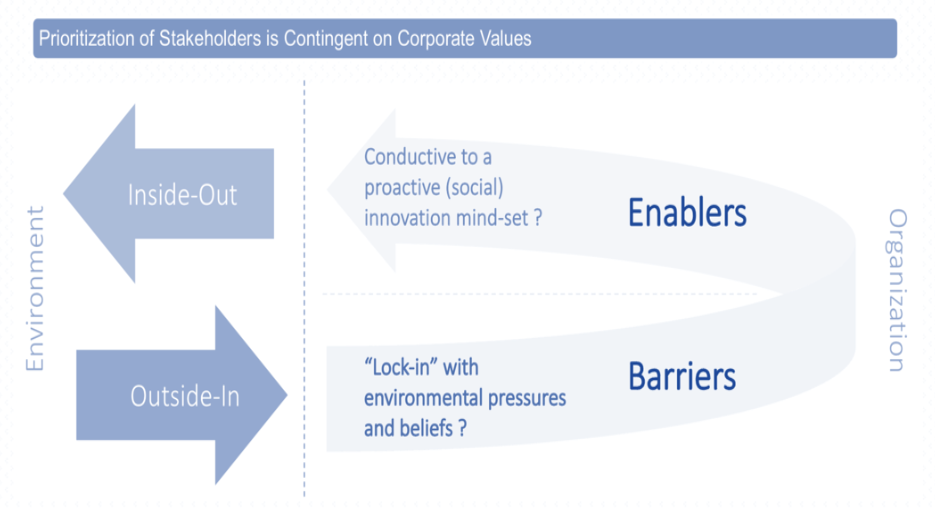

Across our data, our informants emphasized 15 distinctive patterns as ‘enablers of’ and ‘barriers to’ business efforts to effectively address children’s sugar consumption. These perceived enablers and barriers can, broadly speaking, be broken down into two ‘corporate mind-sets’ that crucially affect successes in reducing children’s sugar intake. The common pattern among organizational enablers went along the lines of “The organization itself can and must drive change!”, which we associate with a proactive corporate mindset. The reasoning of the perceived organizational barriers, however, tended to be more like “The organization must foremost account for external demands!”, which we describe as a reactive mindset.

Drawing on the literature on sense-making (Weick 1995) in general, and the notion of “ethical blindness as the result of a sense-making process based on interactions between framing and context factors” (Palazzo et al. 2012: 328) in particular, we suggest that a mere concentration on the second, rather reactive mind-set, mirrors a perceived ‘lock-in’ within external pressures that can be conceived of as a sense-making process that risks to entail a blindness to the ethical dimension (Palazzo, et al. 2012: 324) of organizational priority-setting (i.e. values).

Example: Corporate materiality assessments are one area in which this blindness becomes performative. Although materiality may refer to different things, the outcome of a materiality assessment is often regarded as tangible. We tend to forget, however, that materiality is nothing absolute or objective. Rather, it is constructed on the basis of (often) taken-for-granted organizational processes and priorities. The design of a materiality assessment itself and the definition of materiality as such has thus an enormous influence on the interpretation of the outcomes (Eccles & Krzus 2014). The question that needs to receive more attention is: Which stakeholders’ interests and needs are ‘worthy’ of prioritization beyond their impact on pre-existing strategic targets?

At this point, the case of sugar reduction in children’s food can be transferred to other industries and future investments of resources. The bottom line is, values are performative.

What is valued, gets measured, gets done

Rather unsurprisingly, our findings suggest the following relationship: The success of corporate efforts to reduce children’s sugar consumption is contingent on whether or not child malnutrition is a corporate priority prior to the assessment of environmental influences.

That leads us to question the almost sacred status of the “outside-in” perspective, which has become somewhat of a gold-standard in corporate sustainability management.

Instead of conducting yet another stakeholder engagement workshop, it may actually be more enlightening to scrutinize from the ‘inside-out’ who decides what is (most) valuable to the organization.

This will require strong leadership among executive decision-makers since the implications of corporate strategies cannot be merely delegated to external stakeholders.

Our research shows that a reactive approach risks to foster an organizational “lock-in” and thus tighten barriers to innovations that make a real difference for children’s diet and health. The challenge food and beverage manufacturers and retailers thus face is to avoid this ‘lock-in’ within the preferences, values and beliefs of their environment (such as ‘the persistent consumer demand for sugar products’). This, in turn, implies the need for original corporate values and a mission that is informed, but not determined by their environment, and inspires organizational decision-makers to proactively meet and anticipate social and environmental challenges.

Start with Values

The key-take away from our research is that the future evolution of internal processes within food and beverage retail and manufacturing industry need to be driven by an organizational (social) innovation mind-set (see, e.g. Osburg & Schmidpeter 2013), as well as internally recognized and lived values and priorities (see especially Breuer’s & Lüdeke-Freund’s work on ‘values-based’ innovation management).

Very concretely, a starting point for (more) proactively addressing Children’s Right to a healthy diet could be to ask:

- How can we strategically contribute to a healthier food environment for children, considering the direct and indirect “touch points” we have with children?

- How can we effectively drive the individual and organizational recognition of children’s nutritional health, within and beyond organizational risk management, as a material issue?

- Are our global corporate knowledge management practices aligned with the goal of respecting and supporting Children’s Right to a healthy diet?

- How can we initiate or contribute to collaborations with other stakeholders to reduce children’s sugar consumption

Active Corporate Support for the Children’s Rights and Business Principles

In light of our research, it became clear that against the background of the respect and support framework of the UN, it is not sufficient for corporations to interpret the “respect” for Children’s Rights in terms of ‘doing no harm’. The Children’s Rights and Business Principles define respect as “avoiding any infringement of the Human Rights of others, including children, and addressing any adverse Human Rights impact with which the business is involved” (CRBPs 2012: 5).

The aim of “doing no harm” is insufficient in so far as it implies the existence of a cause-effect relation, which corporations can directly steer. Children’s sugar consumption is, however, influenced by the overall configuration of their food environment. Therefore, there is no such direct cause-effect relation, rendering a mere commitment to do “no-harm” insufficient (see e.g., Schrempf 2014 on the social connection approach to corporate responsibility in the case of the food industry). Rather, food and beverage manufacturers and retailers need to actively support the Child Right to a healthy diet by anchoring positive contributions to social health at the core of their corporate values and operations.

On a more general level, our research demonstrates that an alignment of current food systems with public health objectives is to a large extent contingent on corporations’ capability to innovate and act upon corporate values that put the active support of healthy food systems at the centre of their business practice, i.e. their innovation, marketing and sales activities.

The Authors

Thomas is based in Copenhagen and graduated from CBS in 2018. He studied economics, business administration and philosophy. He enjoys addressing dilemmas and ambiguities of social, economic and business transformation processes. Feel free to connect with Thomas on Linkedin.

Levinia recently graduated from CBS with a MSc in Business Administration & Philosophy. She is passionate about identifying and driving innovative organisational strategies that effectively address the systemic nature of local and global sustainability challenges across value chains. Learn more about what Levinia is up to on Twitter and feel free to be in touch on Linkedin.

References

Breuer, H. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2017): Values-based innovation management – Innovating by what we care about. London: Palgrave.

CRBPs (2012): ‘Children’s Rights and Business Principles’, Save the Children, UNGC & UNICEF. Accessible online.

Eccles, R. G. & Krzus, M. P. (2014): The Integrated Reporting Movement: Meaning, Momentum, Motives, and Materiality. ISBN: 978-1-118-64698-4.

GloPan (2016): ‘Food systems and diets: Facing the challenges of the 21st century’, London, UK.

HLPE (2014): ‘Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems – A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on

World Food Security. Rome.

HLPE (2017): ‘Nutrition and Food Systems – A report by The High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome.

OHCHR (1999): CESCR General Comment No. 12: The Right to Adequate Food (Art. 11) Adopted at the Twentieth Session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, on 12 May 1999 (Contained in Document E/C.12/1999/5), accessible online.

Osburg, T. & Schmidpeter, R. (2013): Social Innovation –Solutions for a Sustainable Future’, Berlin: Springer.

Palazzo, G. et al. (2012): ‘Ethical Blindness‘, Journal of Bussines Ethics, 109: 323–338. DOI 10.1007/s10551-011-1130-4.

Schrempf, J. (2014): ‘A social connection approach to Corporate Responsibility: The Case of The Fast Food Industry and Obesity’, Business & Society, 53(2), 300–332.

Whelan, G. (2017): ‘Political CSR: The Corporation as Political Actor’, in: Rasche, A., Morsing, M., Moon, J. (eds): Corporate Social Responsibility – Strategy, Communication, Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weick, K. E. (1995): Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Photo by Food Photographer | Jennifer Pallian on Unsplash.